Parts-of-speech (also known as POS, word classes, or syntactic categories) are useful because they reveal a lot about a word and its neighbors. Useful for:

labeling named entities

coreference resolution

- speech recognition or synthesis

English Word Classes

Parts-of-speech can be divided into two broad supercategories:

- closed class : with relatively fixed membership, generally function words. The closed classes differ more from language to language than do the open classes

- prepositions

- occur before noun phrases

- on, under, over, near, by, at, from, to, with

- particles

- resemble a preposition or an adverb and is used in combination with a verb

- like up, down, on, off, in, out, at, by

- A verb and a particle that act as a single syntactic and/or semantic unit are called a phrasal verb, the meaning is non-compositional (not predictable from the distinct meanings)

- determiners

- occurs with nouns, often marking the beginning of a noun phrase

- a, an, the, this, that

- One small subtype of determiners is the article: English has three articles: a, an, and the

- conjunctions

- join two phrases, clauses, or sentences

- and, but, or, as, if, when

- Subordinating conjunctions like that which link a verb to its argument are also called complementizers

- pronouns

- often act as a kind of shorthand for referring to some noun phrase or entity or event

- she, who, I, others

- Personal pronouns refer to persons or entities

- Possessive pronouns are forms of personal pronouns that indicate either actual possession or more often just an abstract relation between the person and some object

- Wh-pronouns are used in certain question forms, or may also act as complementizers

- auxiliary verbs

- mark semantic features of a main verb

- can, may, should, are

- copula verb be

- modal verbs do and have

- numerals one, two, three, first, second, third

- interjections (oh, hey, alas, uh, um), negatives (no, not), politeness markers (please, thank you), greetings (hello, goodbye), and the existential there (there are two on the table) among others

- prepositions

- open class: new nouns and verbs are continually being borrowed or created. 4 major in English:

- Noun have two classes: Proper nouns (names of specific persons or entities) and common nouns (count nouns and mass nouns)

- Verbs refer to actions and processes, English verbs have inflections

- Adjective includes many terms for properties or qualities

- Adverb , is rather a hodge-podge in both form and meaning, each can be viewed as modifying something

- Directional adverbs or locative adverbs (home, here, downhill) specify the direction or location of some action;

- Degree adverbs (extremely, very, somewhat) specify the extent of some action, process, or property;

- Manner adverbs (slowly, slinkily, delicately) describe the manner of some action or process

- Temporal adverbs describe the time that some action or event took place (yesterday, Monday)

The Penn Treebank Part-of-Speech Tagset

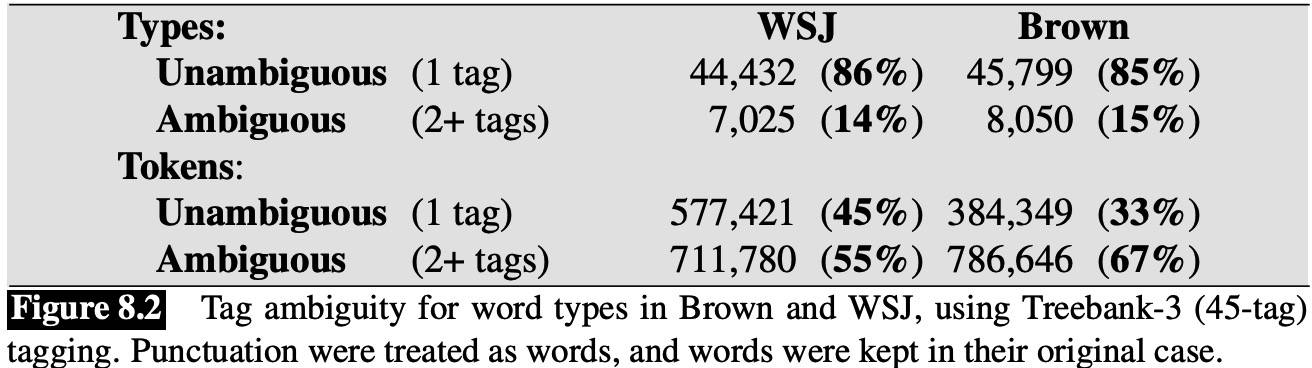

main tagged corpora of English

- Brown: a million words of samples from 500 written texts from different genres published in the United States in 1961

- WSJ: a million words published in the WSJ in 1989

- Switchboard: 2 million words of telephone conversations collected in 1990-1991

Part-of-Speech Tagging

Part-of-speech tagging is a disambiguation task, words are ambiguous. Some of the most ambiguous frequent words are that, back, down, put and set.

Most Frequent Class Baseline: Always compare a classifier against a baseline at least as good as the most frequent class baseline (assigning each token to the class it occurred in most often in the training set).

HMM Part-of-Speech Tagging

The HMM is a sequence model.

Markov Chains

A Markov chain is a model that tells us something about the probabilities of sequences of random variables, states, each of which can take on values from some set.

Markov Assumption:

Formally, a Markov chain is specified by:

- a set of N states:

- a transition probability matrix A, each aij representing the probability of moving from state i to state j:

- an initial probability distribution over states, πi is the probability that the Markov chain will start in i:

The Hidden Markov Model

A hidden Markov model (HMM) is specified by:

- a set of N states:

- a transition probability matrix A, each aij representing the probability of moving from state i to state j:

- a sequence of T observations, each one drawn from a vocabulary

- a sequence of observation likelihoods, also called emission probabilities, each expressing the probability of an observation ot being generated from a state i:

- an initial probability distribution over states, πi is the probability that the Markov chain will start in i:

A first-order HMM instantiates two simplifying assumptions:

- Markov Assumption:

- Output Independence:

The components of an HMM tagger

A matrix represent the probability of a tag occurring given the previous tag:

B emission probabilities represent the probability given a tag that it will be associated with a given word:

HMM tagging as decoding

The task of determining the hidden variables sequence corresponding to the sequence of observations is called decoding: Given as input an HMM λ=(A,B) and a sequence of observations O, find the most probable sequence of states Q.

The goal of HMM decoding is to choose the tag sequence that is most probable given the observation sequence of n words:

HMM taggers make two further simplifying assumptions:

- the probability of a word appearing depends only on its own tag and is independent of neighboring words and tags:

- bigram assumption, the probability of a tag is dependent only on the previous tag, rather than the entire tag sequence:

- B emission probability:

- A transition probability:

The Viterbi Algorithm

As an instance of dynamic programming, Viterbi resembles the minimum edit distance algorithm.

1 | function VITERBI(observations of len T, state-graph of len N) returns best-path, path-prob |

The code is here.

- the previous Viterbi path probability from the previous time step:

- the transition probability from previous state

qito current stateqj: - the state observation likelihood of the observation symbol

otgiven the current state j:

Expanding the HMM Algorithm to Trigrams

In practice we use the two previous tags:

That increases a little performance but makes the Viterbi complexity from N hidden states to N×N.

One advanced feature is adding an end-of-sequence marker:

One problem is sparsity, the standard approach to solving this problem is the same interpolation idea

we saw in language modeling smoothing:

λ1 + λ2 + λ3 = 1, λs are set by deleted interpolation.

1 | function DELETED-INTERPOLAtiON(corpus) returns λ1, λ2, λ3 |

Beam Search

One common solution to the complexity of Viterbi is the use of beam search decoding: just keep the best few hypothesis at time point t. Beam width β is a fixed number of states.

The code is here.

Unknown Words

Unknown words often new common nous and verbs, one useful feature for distinguishing parts of speech if word shape: words starting with capital letters are likely to be proper nouns (NNP). Morphology is the strongest source of information, we are computing for each suffix of length i the probability of the tag ti given the suffix letters (P(t_i|l_{n-i+1}...l_n), then use Bayesian inversion to compute the likelihood p(wi|ti).

It is not suitable for Chinese. In Chinese, a name is often starting with a surname, but it’s not helpful for some cases. For example, the surname “王”, there are many common words starting with it: “王子 王位 王八 王八蛋…”, we can not distinguish them without their context. So most time we have use a model or a big dict to solve the problem.

Maximum Entropy Markov Models

MEMM is maximum entropy Markov model, compute the posterior P(T|W) directly, training it to discriminate among the possible tag sequences:

HMMs compute likelihood (observation word conditioned on tags) but MEMMs compute posterior

(tags conditioned on observation words).

Features in a MEMM

Using feature templates like:

Janet/NNP will/MD back/VB the/DT bill/NN, when wi is the word back, features are:

1 | ti = VB and wi−2 = Janet |

Also necessary are features to deal with unknown words:

1 | wi contains a particular prefix (from all prefixes of length ≤ 4) |

Word shape features are used to represent the abstract letter pattern of the unknown words. For example the word well-dressed would generate the following non-zero valued feature values:

1 | prefix(wi) = w |

The result of the known-word templates and word-signature features is a very large set of features.

Generally a feature cutoff is used in which features are thrown out if they have count < 5 in the training set.

Decoding and Training MEMMs

Input word wi, features will be its neighbors within l words and the previous k tags:

Greedy decoding builds a local classifier that classifies each word left to right, making a hard classification of the first word in the sentence, then the second, and so on.

1 | function GREEDY SEQUENCE DECODING (words W, model P) returns tag sequence T |

The problem is the classifier can’t use evidence from future decisions. Instead Viterbi is optimal for the whole sentence.

- HMM:

- MEMM:

Bidirectionality

One problem with the MEMM and HMM models is that they are exclusively run left-to-right. While the Viterbi still allows present decisions to be influenced indirectly by future decisions, it would help even more if a decision about word wi could directly use information about future tags t_{i+k}.

MEMMs also have a theoretical weakness, referred to alternatively as the label bias or observation bias problem. These are names for situations when one source of information is ignored because it is explained away by another source.

The model is conditional random field or CRF, which is an undirected graphical model, computes log-linear functions over a clique (a set of relevant features might include output features of words in future time steps) at each time step. The probability of the best sequence is similarly computed by the Viterbi.

CRF normalizes probabilities over all tag sequences, rather than all the tags at an individual time t, training requires computing the sum over all possible labelings, which makes training quite slow.

Part-of-Speech Tagging for Other Languages

While English unknown words tend to be proper nouns in Chinese the majority of unknown words are common nouns and verbs because of extensive compounding. Tagging models for Chinese use similar unknown word features to English, including character prefix and suffix features, as well as novel features like the radicals of each character in a word.

Summary

- A small set of closed class words that are highly frequent, ambiguous, act as function words; open-class words like nouns, verbs, adjectives.

- Part-of-speech tagging is the process of assigning a part-of-speech label to each word of a sequence.

Two common approaches to sequence modeling are a generative approach, HMM tagging, and a discriminative approach, MEMM tagging.

The probabilities in HMM taggers are estimated by maximum likelihood estimation on tag-labeled training corpora. The Viterbi algorithm is used for decoding, finding the most likely tag sequence. Beam search maintains only a fraction of high scoring states rather than all states during decoding.

Maximum entropy Markov model or MEMM taggers train logistic regression models to pick the best tag given an observation word and its context and the previous tags, and then use Viterbi to choose the best sequence of tags.

- Modern taggers are generally run bidirectionally.